_edited.png)

The 36th Division Archive

Corporal William L. Bryant

.30 Caliber Machine Gunner, Machine Gun Squad Leader

M & K Company, 3rd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division

William “Bill” Louis Bryant was born in the rural town of LaGrange, Kentucky just east of Louisville in May of 1922. His mother, from Oldham County, and his father, from Shelby County, lived there for a brief period before moving to Louisville in the late 1920s after the birth of William’s brother, Joe. There his father got a job as a fireman with the American Radiator & Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Company, which operated a major plant in the city making bath fixtures of various types. At first they lived near East Woodlawn Avenue but, after the Great Louisville Flood of 1937, moved south to the Shively Area. It was for good measure, as their former property was redeveloped by the Army Corps of Engineers into Standiford Field, now Louisville’s SDF International Airport.

Brought back by William as a souvenir, it is a size medium dated 1942.

William entered DuPont Manual High School in 1936, a well-respected technical training institution in the heart of Louisville. While here he was drawn to more mechanical type trades, such as wood shop, machine shop, bookkeeping, and other more industry-based courses. In his free time he also enjoyed playing on their baseball team. Unfortunately, he did not graduate but instead dropped out after his junior year to begin his career. Although his father had moved on to a new job as a painter, William took up his former employment, joining American Radiator as a shipping and receiving clerk to help oversee their logistical operations. It was not long after working in this role that the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, dragging the United States into war. Less than a year later, on September 16, 1942, William decided to do his part by enlisting in the United States Marine Corps.

With his limited work experience in logistics, William first asked the Marines to place him in a quartermaster or supply role. The Corps, as it often does, decided William was better fit for an assuredly similar task: machine gunner. He underwent basic training in San Diego, California, and graduated as a .30 caliber light machine gun gunner, MOS 604. On November 11, 1942, he received his assignment to M Company, 3rd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division which was forming at Camp Pendleton. The 9th Marine Regiment had only been formed earlier that year and at the time he joined, was going through intense combat training for service in the Pacific Theater. For several months he participated in this effort until the 9th Marines were sent off for Auckland, New Zealand aboard the USS Mount Vernon on January 24, 1943.

Arriving in early February, the men were billeted across the island because no single facility could hold the thousands of fresh marines filling the country. Over the next few months they underwent more advanced unit exercises, learning tropical survival skills and specializing in the unique facets of jungle warfare. By June the regiment was ready to move to Guadalcanal aboard the USS American Legion, arriving to set up a large base camp for further jungle training, maintain facilities on the island, and perform general prep work for whatever future combat they might be involved in. In October word spread that they might be moving out soon and on October 22 the possibility became real as the regiment loaded up once again aboard a Coast Guard transport, the USS Hunter Liggett, for a week of amphibious assault exercises at Efate, New Hebrides Islands. The most intense and involved practice the men had gone through yet, they left the training area on October 28 with excited chatter filling the ship’s berth. Something big was coming. Finally, the announcement came that they were indeed ready to receive their baptism of fire on the South Pacific island of Bougainville.

Bougainville, the largest land mass of the Solomon Islands chain, was home to numerous Japanese air, naval, and army bases since they first invaded early in 1942. To help break up this foothold in the Southwest Pacific and create new airfields for allied aircraft striking further into Japanese territory, the U.S. military believed that an amphibious landing on the island’s western Cape Torokina and Empress Augusta Bay, weakly defended parts of the island due to extremely harsh physical jungle and mountain terrain, might prove fruitful. After several days at sea, a steak and eggs breakfast greeted the marines aboard the Hunter Liggett on the morning of November 1, 1943. Around 0730 William and his fellow marines, with bellies full and gear strapped, climbed down the netting on the side of the ship into their LCVP landing craft. The three battalions of the 9th Marines landed in numerical sequence on the far left flank of the division beachhead. William’s battalion landed on the beach designated Red 1, a rather short strip of sand butting up to a steep overhang near the Koromokina River. There was no Japanese resistance during the landing and most difficulty came in getting out of the boats themselves, as they had to turn sideways due to the short depth of the sand and rough waters. Running out of their landing craft to find little else but jungle, the marines walked inland and set up defensive positions in the swampy terrain.

The first few days after the landing were mainly spent patrolling the nearby jungle. On November 3, however, the 1st and 2nd Battalion of the 9th Marines were sent away from the landing zone towards the far right of the division line, where heavy fighting was taking place. This left William’s battalion the sole unit holding the extreme left flank of the entire 3rd Marine Division, curving their defensive line all the way into the sea. Without the rest of the regiment to support, 3rd Battalion reinforced their positions, using machine gunners from M Company like William to create strongpoints along the battalion line. The build-up earned its keep on November 7 when the first sight of Japanese troops signaled a new phase in the invasion for 3/9.

Early in the morning, around 0600, four Japanese destroyers entered Atsinima Bay and sent landing craft towards the shore. First spotted by an anti-tank crew of 3rd Battalion, the enemy troops, around 500 from the Japanese 54th Infantry Regiment, landed further down the beach past the 3rd Battalion lines. K Company, holding the farthest left flank, as well as a machine gun outpost of William’s company set out in front of them, was given the job of dealing with this threat. The marines knew that they had some time while the Japanese soldiers struggled to coordinate themselves in the dense jungle. One patrol of K Company moved out towards the Laruma River to try and tease out the landing forces. The first engagement came when two Japanese boats landed only 400 yards from the 3rd Battalion line, quickly moving to attack the American positions only to be mowed down by machine gun, rifle, and artillery fire. The first blood had been shed by the 3rd Battalion.

At this point, at around 0820, K Company decided to immediately counterattack towards the main Japanese force. Despite the heavy artillery support from gun batteries in the American sector, the Japanese successfully placed themselves in the former defensive positions of 1/9 and 2/9, who occupied the area for the first few days after the landing. Combat was fierce for two days, often hand to hand, rifle to rifle, and grenade to grenade. At the same time the Laruma River patrol made contact, finding a much larger Japanese force. On their retreat back to the lines they were able to fight off some chasing Japanese troops, in one instance with help from some of the M Company machine gun outposts. By the end of the engagement the marines had shored up the line and waited for further action. The third morning found airstrikes hitting the main body of the Japanese force, causing heavy casualties and sending the enemy troops on a full retreat. Marines probing for their line only discovered empty holes and scattered corpses. William’s battalion had met the enemy in the battle of Koromokina Lagoon, and won.

With the Japanese threat to the left flank repelled, 3/9 was replaced by elements of the 21st Marines and the army’s 37th Infantry Division. Sent back to the 9th Marines in the Cape Torokina sector, they inhabited the rear of the division’s right flank. For the next ten days the regiment advanced slowly inland to the east in order to secure ground for a future airfield, setting up new defenses along the expanded perimeter. On November 20, 3rd Battalion moved up alongside the Numa Numa and Piva trails, fighting scattered Japanese forces in pillboxes and dugouts east and west of the main trails. This was followed with an advance of the entire regiment about a thousand yards east of the Piva River while most of the heavy fighting was centered around the 3rd Marine Regiment nearby. Lugging his machine gun through the jungle, William did not experience too much heavy fighting at this point, mostly moving back and forth between defensive positions to ensure no Japanese troops could flank around the side of the division while the heavy action along the east-west trail was taking place. This was the role of 3rd Battalion for the final week of November.

December began with little worry for Japanese assaults. The other regiments of the division had won a decisive victory along the main trails to push back the largest Japanese force. William’s battalion spent the first two weeks near Hill 1000, a land mass next to the more infamous “Hellzapoppin Ridge,” the site of much fighting between the Japanese and other marine regiments. Most emplacements they encountered were full of dead Japanese, who they buried, and a number of abandoned weaponry. Digging in permanently on December 9, they built reinforced positions, put down mines and wires, and spent the rest of the month sending patrols around the area with scattered skirmishes against Japanese remnants. The army came into the area on December 27, taking over their positions and sending the marines back to the beach. Here William and his buddies each received two cans of warm beer as they boarded the USS President Adams, leaving their first battlefield for an encampment on Guadalcanal.

Disembarking at Guadalcanal on December 30, the new year of 1944 brought little relief for the men of the 3rd Marine Division as they began a new bout of training for a planned landing on Kavieng, on the northern tip of New Ireland. William, experienced in more defensive warfare at Bougainville, trained now for urban combat as a large city was expected to be the center of their assault on the island. In April 1944, right before the operation was to go underway, the entire plan was scrapped and the marines told to stand down. A new target was in sight for the marine leadership: Guam. Around this time William also received a promotion, to corporal, and became a machine gun squad leader, commanding a five-man machine gun team. He also received a transfer to K Company of 3/9, leaving behind his long-time friends for the new leadership role.

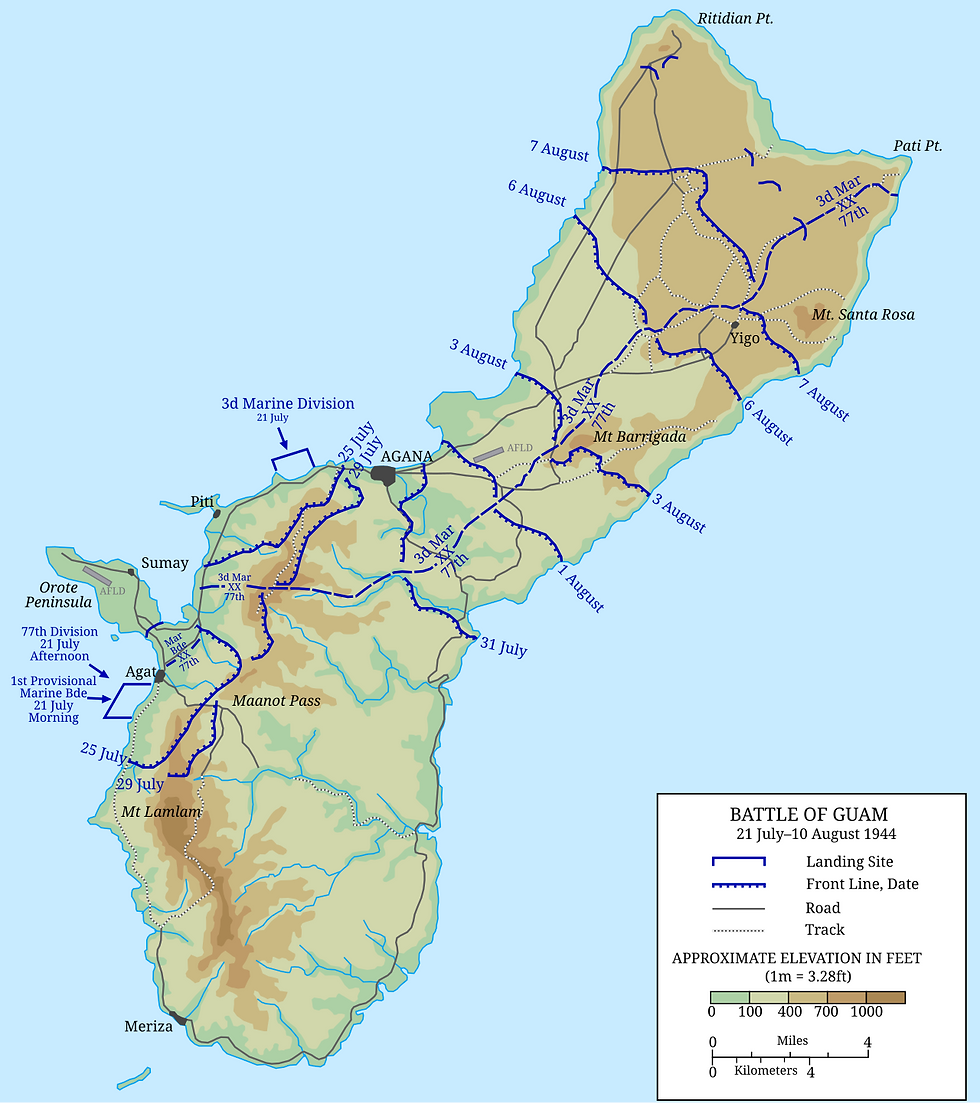

In this capacity he spent April and May training alongside his machine gun team, including in a division-wide practice landing at Cape Esperance. On June 2 the regiment loaded up, leaving their well-used camp behind, aboard the USS President Adams, arriving in Kwajalein six days later. They had to wait around on the island for several weeks while plans and operations shifted for the invasion. On July 1 they finally went aboard their intended landing craft, USS LST-488, but waited for nearly two weeks before finally setting sail. While en route, William learned of the D-Day invasion of France, discovering that progress was being made on invasions all the way across the world while he prepared for his next one. By July 20 they reached the island of Guam and made ready for their biggest fight yet.

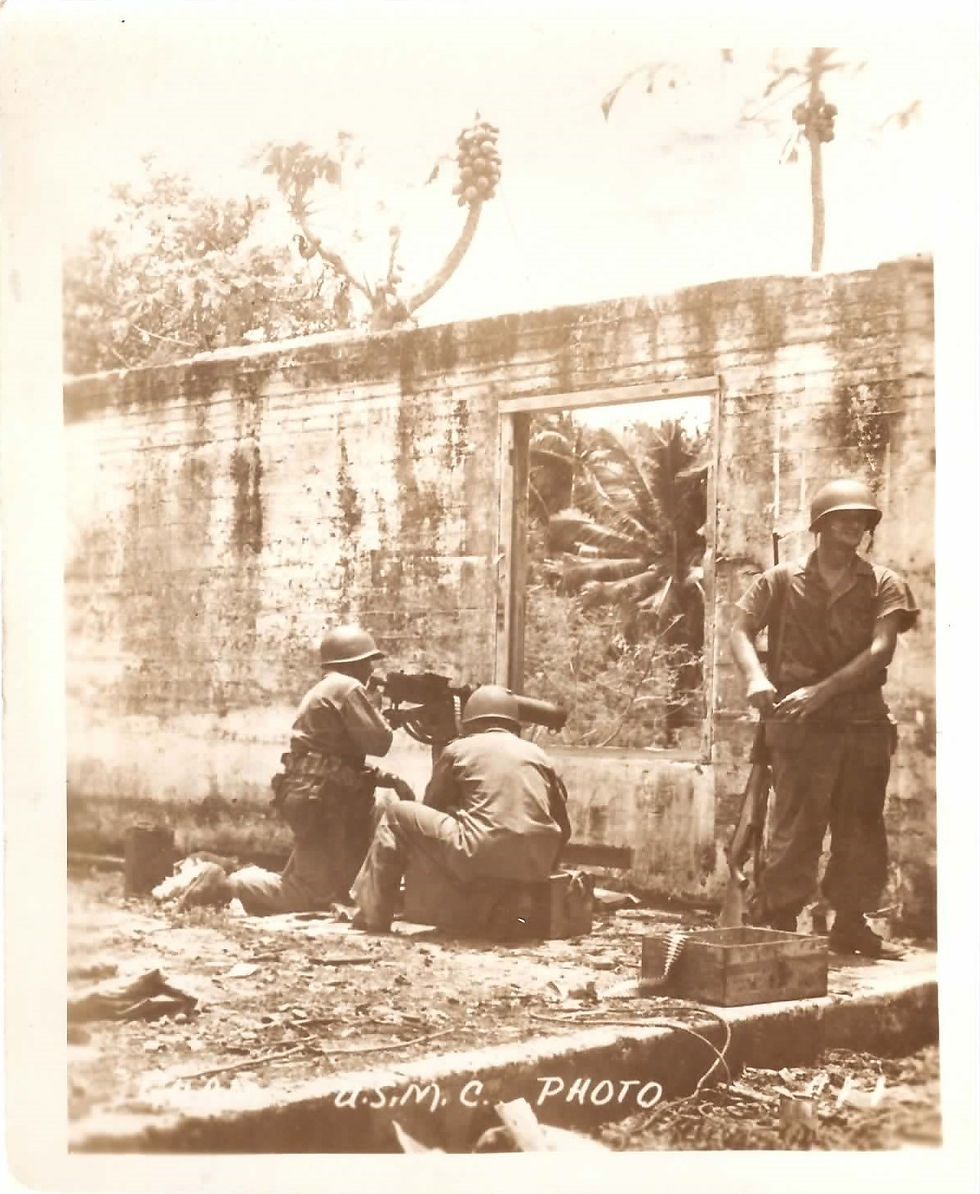

Guam, the largest island of the Marianas, was a U.S. territory captured by the Japanese days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The planned invasion, coordinated with the nearby invasion of Saipan, sought to take it back. Before William and his comrades made their landing, nearly 300 ships and a number of planes launched tens of thousands of shells onto Japanese positions. At daybreak on July 21, 3rd Battalion loaded into their tracked amphibious landing vehicles, or “amtracs,” and began making their way ashore through the heavy coral reef surrounding the island. The 3rd Battalion landed on Blue Beach, between the Asan River and Asan Point, at 0830. While the Japanese concrete buildings and defenses right along the beach seemed destroyed by the bombardment, a large ridge overlooking the entire landing zone still had plenty of Japanese guns intact which began raining down heavy fire upon the marines. 3rd Battalion was in the thick of this barrage when they began receiving fire from Asan Point, requiring the use of supporting Sherman tanks to try and repel the enemy fire. As quickly as they could they tried to push inland, driving over the initial landing zone to the rice paddies beyond. Despite a bloody first day, the battalion nearly reached its objective before serious resistance was found, requiring them to dig in around 1830.

Most Japanese resistance appeared to come from various caves on Asan Point and the large ridge overlooking the beachhead. The 9th Marine advance continued the next day towards the former American naval base at Piti, along Apra Harbor, and Cabras Island, a small thin strip just off the coast. Although bitterly defended by the Japanese, the objectives were taken. William and his battalion had the unique mission of taking Cabras Island all by themselves, landing on its beaches in amtracs in the afternoon. Combat was minimal in the operation, however, with most of their troubles coming from the hundreds of mines and bramble fields adorning the island. Over the next two days the regiment mostly patrolled into enemy territory, slowly progressing through open fields and hills at night worried that the Japanese might occupy and fortify them. On July 25 the entire division launched a large assault against the main ridgeline, taking the high ground by the evening and digging in. A major objective to secure the landing zone, spirits were high but soon to be tempered.

While William was sitting alongside his machine gun team in a foxhole that night, nearly 5,000 Japanese soldiers were getting rabidly drunk on sake, whipping themselves into a bloody frenzy. With scattered probes testing the marines in the early morning hours, what followed was the largest Japanese attack the division had seen as thousands of Japanese troops initiated a mass banzai charge at 0400. Fire erupted up and down the entire division line with artillery support called in by nearly all units on the front. The Japanese troops, attacking from nearby Mount Tenjo, threw themselves in human waves against the division, breaking through in a number of critical areas. During the attack, William recalled sitting along the high ground overlooking the 2nd Battalion of the 21st Marines which was directly to his left. Between his outpost and 2/21 was a river ravine running through the ridge and within it, hundreds of Japanese soldiers trying to break through the line. Without second thought he “moved his .30 caliber machine to his left and set up in a position overlooking 2/21’s lines” and began to open fire, pouring belt after belt of ammunition into the stream of enemy troops. According to later accounts, William remained in his spot continuing to “inflict[] heavy casualties” upon the attackers for nearly two hours before his company commander gave the orders that they were to fall back and plug a breach forming near the 1st Battalion command post. They arrived “in the nick of time” to help drive back the Japanese there and, after several more hours of fighting, watched as daylight streamed over the ridge, shining down upon thousands of Japanese bodies which littered the battlefield. Despite the incredible brute force of the assault, William and the two neighboring regiments accounted for over 3,000 Japanese dead.

Spending an entire day cleaning up from the incredible defense, an army unit was sent up to relieve 3rd Battalion on July 27, taking most of the marines back to an assembly area for some rest. William’s company, however, was picked to stay up front with the 21st Marines to help clear out a number of caves in the rear of the 21st’s right flank. Japanese from the attack had wedged themselves inside and the day was spent flushing them out, William’s machine gun no doubt playing its part. The 9th Marines continued their attack the day after, up towards Mount Alutom and Mount Chachao, with the 21st Marines on the left flank. The advance was a success but 3rd Battalion encountered a particularly heavy strongpoint at the base of Mount Chachao, calling down artillery while William and his comrades attacked in close quarters, using grenades, bayonets, and “destroy[ing] everything that stood in their path.” It was brutal fighting which left all of the Japanese defenders dead. Moving up onto the ridgeline, the battalion claimed another successful day of combat while the Japanese fell into a massive retreat. At dawn the regiment moved towards Hill 532 with 3rd Battalion sending out several patrols that mostly found Japanese soldiers caught behind the American lines trying to escape. Delaying forces from the main body of enemy troops also caught the battalion, but the momentum was strong. Two more days of continued pushing found the entire division driving the Japanese northward towards the sea.

On July 31 the 3rd Battalion attacked abreast of 1st Battalion, encountering small groups of enemy at first that led to heavier resistance, including Japanese tanks, by the afternoon. 1st Battalion met the bulk of the enemy force so 3rd Battalion worked around them, seizing key parts of the Agano-Pago road which the entire regiment would claim by the end of the day. This highway would later prove key to seizing Guam as a logistical necessity for keeping up the attack. The next week of fighting was slower but just as successful, taking the Tiyan Air strip and maintaining a tight line of advance with the 1st Battalion to keep taking ground in the northern stretch of the island. The jungle soon began to get thick, however, and at times Japanese troops and tanks would be within fifteen yards before marines would see them. William’s company was on the farthest left flank of the advance and was thus important in closing the gap between the 9th and 21st Regiment in spite of the harsh terrain. Nevertheless, the Japanese continued racking up massive casualties with tons of enemy equipment slowly falling into marine hands. On August 7 the final push took place as the 9th Marines advanced up the jungle trails, 3rd Battalion in the rear and reserve while the other two battalions fought off some Japanese stragglers and remaining points. By the end of August 9, they reached the ocean, no more enemy to be seen.

With the initial phase of Guam complete, William and the other marines were given a well-deserved rest near Ylig Bay in a large coconut grove where they set up camp. For two months they enjoyed the shade it brought them, improving their huts and facilities while the army took the job of patrolling the island for remaining Japanese. At the end of October, however, reports of Japanese survivors forming larger bands once again in the northern edge of the island led the entire 3rd Marine Division to perform a full island-wide sweep. Lined up with all three regiments abreast, from October 24 to 31 the men marched through open terrain, dense underbrush, and thick jungle in skirmish lines, flushing out group after group of surviving Japanese soldiers. Many of the remaining enemies were in poor shape, some fighting with bayonets or hand grenades only. On the final day half a dozen Japanese were killed going down the final cliff towards the waterfront and by November 1, the patrols were over. Their job on Guam was done and for the next three months the marines enjoyed some downtime and training.

It was not until February 1945 that the 3rd Marine Division was re-upped for combat service, this time for one of the most ambitious operations yet: Iwo Jima. Embarking upon the USS Leedstown on February 9, the marines left Guam seven days later en route to the porkchop-shaped island. Arriving offshore on the 19th, William and his comrades spent three days watching the initial assault while in floating reserve, seeing the brutal bombardment on the beach, the struggle inland, and one of the more inspiring moments, the flag raising on Mount Suribachi. Reflecting on the flag, William later recalled that he was not “overwhelmed with patriotic pride” but instead “wondering whether he could make it off the island alive.” A fitting concern for a marine who had survived both Bougainville and Guam unscathed.

The regiment disembarked on February 23, receiving orders from their Captain, Bill Crawford, that their initial objective was to gather at the edge of Motoyama Airfield No. 1 and await further instruction. Many of the replacements were impatient and anxious to get in the fight, while the veterans like William knew what they were getting into did not look good. “When we went ashore it looked like black sand, but it was volcanic ash,” he remembered, as the operation quickly became “two steps forward and one step back all the way.” William wrote later of the countless dead and broken bodies he saw strewn across the beach, evacuees and casualties from the first few days of the fight. The flat terrain quickly demonstrated how this was possible, as little protection existed on top of the island with the most cover coming from the shell craters littering the landscape.

Reaching their first objective fairly quickly, K Company received orders to advance through another company that was pinned down between Airfield 1 and 2, with the objective to capture the second airfield. This was when the real battle began. Spending the night at the base of Airfield No. 2, “[m]ortars and artillery shells rained over us all night long.” Most demoralizing, however, were the “buzz-booms,” formally known as the Type 98 320mm mortar. These guns, fixed in various locations around Iwo Jima, fired a massive “screaming” 660-lb projectile which left an eight-foot-deep and fifteen-foot-wide crater. The round itself was roughly the size of a small refrigerator. This was the first William recalled ever learning about these artillery pieces which “sounded like freight trains” throughout the night.

The next day was full of similar back and forth action, with William guiding his machine gun team to provide suppressing fire against near-hidden and well-entrenched Japanese troops. Around 1600 on February 25, however, their company joined with two battalions of the 21st Marines to advance onto the airfield. Moving with three M4 Shermans of the division tank battalion, Captain Crawford gave William the job of watching the anti-aircraft guns on the hill in front of them. “I told him there weren’t any Japs near the guns, then some did appear from a cave that had a steel door cover.” At that moment, just as the Captain began to make his way to another part of the line, “all hell broke loose.” Enemy mortars, artillery, machine guns, and rifles opened up on the advancing marines. Nearly 800 Japanese bunkers were nestled in the 1,000-meter long emplacement they were hitting, the heart of the defensive line. William was manning his gun watching as Captain Crawford immediately took a Japanese bullet to the head, falling across the machine gun of Private First Class Vernon Huckaby. A corpsman tried to provide aid but the still-conscious Crawford ordered him to leave him alone and help others. Regardless, the corpsman dragged him behind a rock where he died. He had led K Company through all of its campaigns and was highly respected among the men.

Despite the loss of their commanding officer, William and K Company continued to press the attack. “Enemy mortars, larger than we had ever seen, knocked out our three tanks” he recalled, “it looked like half of our numbers were hit.” Amidst the barrage, a piece of shrapnel hit William. Feeling pressure on his back, he asked his number one gunner, Corporal David Guess, to check him out. As it turns out, a piece of shrapnel had torn through William’s field pack and buried itself three inches down from his shoulder near his spine. Guess pulled the jagged piece of metal out of his squad leader without a hitch. Despite the shrapnel’s proximity to paralyzing William, he was “still on my feet and going.” The close call did leave a large burn on his back, however, which remained for the rest of his life.

William happened to be one of the lucky ones that day, as casualties mounted for the company. The following descriptions are in William’s own words, detailing the intensity and gore of the combat on Iwo Jima:

Shortly after [the shrapnel hit me], I felt something hit my helmet. I moved my head to the side. After another blast, I reached up and realized it was [PFC] Joe Haas’s brains that had hit my helmet. He was some forty or fifty feet from me. Joe, also, was a machine gunner.

I went over to help the wounded and the first person I saw was [Gunnery Sergeant] Jim Boman. He had been wounded and was holding his intestines with his left hand and arm while helping his people who had been wounded. I said that he should go to the corpsman, but his reply was, “Not until I get all my wounded out of here.”

It was mass destruction–wounded and dead all over. I found [Sergeant Elmer] “Dick” Schrieber, a machine gun section leader, still alive, but with his left kidney blown out. I asked for help to get him back to the first aid station. After getting him to the station, I came back.

While Sergeant Boman miraculously survived his wounds, Schrieber’s proved fatal. He passed away in the aid station the next day. The fighting at Iwo Jima was like nothing the men of K Company had ever seen. As described in the title of K Company Lieutenant Patrick Caruso’s postwar book, it was a “nightmare.”

On February 26, 1945, while K Company was still fighting over the airfield, William’s luck ran out. Although he did not recall the event due to the trauma inflicted, other veterans of K Company attested that on this day one of the large rounds from a 320mm Type 98 mortar landed near William, throwing him nearly seventy-five feet through the air. Somehow surviving the blast, he was evacuated, fully unconscious, to the beach where the battalion surgeon determined he had a “favorable” chance of recovering. On the next day he was loaded into an LCVP and taken to the USS Logan, an APA transport acting as a hospital ship for wounded marines. The medical staff on board concurred with the surgeon’s finding, noting that he had received a severe concussion blast to the head, abdomen, and back. They did not record, however, the shrapnel wound which was certainly still present on his shoulder. William woke up two or three days after the blast while aboard the Logan and was tended to by the shipboard staff until they arrived at Guam where he was admitted to Fleet Hospital No. 111, taking about a month to fully recover.

By the end of combat on Iwo Jima, only six of the original 210 men who landed with K Company were not wounded or killed. For their heroism in the capture of the airfield, the 9th Marines were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, which read in part:

For extraordinary heroism in action with the enemy during the operation for Iwo Jima, Volcanic Islands, from 25 February to 16 March 1945. During the period 25 February to 16 March the 9th Marines operated continuously in the front lines in combat against the enemy. Attacking on the morning of 25 February, the 9th Marines in a furious three-day assault shattered the enemy’s main line of resistance north of Motoyama Airfield No. 2, decisively cut his communications, and rendered inevitable the final success of the campaign. That success was gained in spite of terrain which conferred every advantage to the defenders, and in the face of positions prepared by the enemy with every artifice, every installation, and every weapon available to provide a defense as nearly invulnerable to assault as enemy ingenuity could devise. The cost of that success in casualties was more severe than that in any other single action in which the division participated. Every company commander and a crippling proportion of other key personnel were killed or wounded. In the normal course of human experience, the Regiment could not have been expected soon again to wage a vigorous campaign, but, resuming the attack on the following day, the 9th Marines continued a steady advance

In early April, while William was still recovering, his mother, now a Red Cross nurse, wrote a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that she had not heard anything about William other than the fact he was hit at Iwo Jima. “I have no idea as to his condition and it is worrying his father and I beyond words to express,” she explained. She requested that the President approve some sort of furlough for William since he was never able to get one before going overseas with the 3rd Marine Division. In the three years since his enlistment, he had never once been home. His brother, Joe, had also joined the marines and served in the 6th Defense Brigade. Begging for some peace, she asked if her “wounded boy,” William,” could at least come home. Although answered by military officials that this was likely impossible, she did not have to wait too much longer as William returned to Louisville in May, bringing with him his basic belongings, a souvenir Japanese cap he had taken from one of his many campaigns, and a number of visible and invisible wounds.

Waiting out the rest of the war back in the United States, William finally married his lifelong bride, Virginia, on June 9, 1945 and remained on the marine casualty company list until he received his official discharge from the Marine Corps in October. By the end of the war Wiliam had spent an impressive twenty-seven and a half months overseas, receiving the Purple Heart, Presidential Unit Citation, and three Pacific campaign stars. Returning to his trade roots, he began a long career as a planner and foreman at Louisville General Electric (GE) while his wife worked in the U.S. Census Bureau. This lasted until 1972 when William got roped into a fraud scheme with a subcontractor of GE, inflating their bills and splitting the profits. He was able to avoid a long jail sentence, however, by pleading to fourteen days plus a return of the over $21,000 they had taken.

Beyond his professional mishaps, William struggled the rest of his life with what he had experienced overseas. Like many World War II veterans, he suffered in silence from post-traumatic stress disorder for years. In his own postwar reflection on Iwo Jima, he wrote that

Iwo was the worst. A few days on Iwo are capable of a lifetime of haunting memories… all men of K Company were affected by this campaign, even those who were not wounded. Anybody who says this wasn’t frightening isn’t being truthful. We are all still affected, maybe not physically, but in our minds, the memories haunt us.

William’s granddaughter wrote a letter for his entry in Caruso’s book on the campaign and further explained that

It has just been in the last five to ten years that my grandfather has begun to release the fear of his experiences. We have all lived with the symptoms of his fears, but we are just realizing how deep his psychological and emotional scars have been, how strong his psychological defense mechanisms have been, and how his behaviors were affected by the hell of war. He remains “semper fi.”

The wounds of war proved more than skin deep.

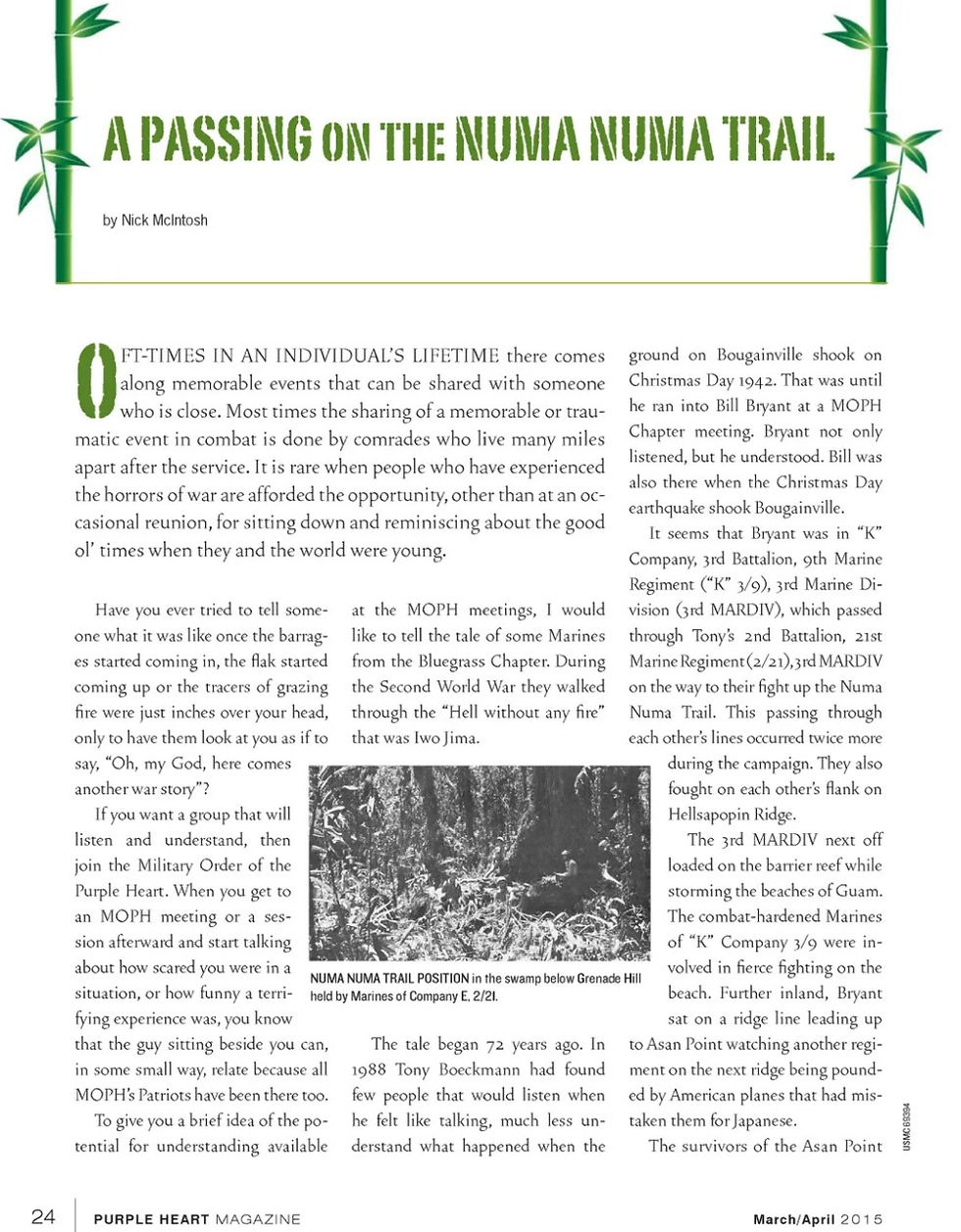

One of the most healing moments for William came when he joined the Bluegrass Chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart. A veteran’s organization for those who received the medal for wounds in action, William bonded with dozens of other local servicemen who had borne the physical and emotional scars of combat. He found the organization a safe place for him to share the fears and terrors he had felt during his time overseas and to find comradery in the experiences of others. One of his closest friends became Tony Boeckmann, a marine of 2nd Battalion, 21st Marine Regiment, who had fought through all three of the same campaigns right alongside William. Unknowingly, that had lived only four blocks away for nearly their entire adult lives but not until meeting in the Order did they begin to bond over brotherhood in battle.

William passed away in Louisville surrounded by his loved ones in May of 2009. A lifelong Kentuckian, William answered his country’s call by volunteering for the United States Marine Corps, spending over two years in the Pacific fighting across the jungles, mountains, and black sands of World War II’s bloodiest battlefields. A wounded warrior, physically and psychologically, he nevertheless pressed onward to create a meaningful career and family. Even more, his testimony and friendship helped to heal other fellow veterans united in their shared experiences.